Padding Oracle Vulnerabilities Under The Hood - Part 2: Attack

1. Introduction

You can find first part of this blog post there:

This blog post covers the following;

- Overview of The Exclusive-OR and some of its tricks.

- The Padding Oracle Attack under the hood.

- A demo padding oracle attack script against our demo application which was introduced on Part-1.

- A few tricks and tools for penetration testers in order to do assesments and exploitation for Padding Oracle Vulnerabilities.

- Recommendations.

2. Revisiting The Exclusive-OR

Let’s take a step back and remember the Exclusive-OR truth table:

INPUT—OUTPUT

A–B——A-XOR-B

0–0————0—–

0–1————1—–

1–0————1—–

1–1————0—–

As seen above, it gives ‘1’ when values are different.

XOR can be represented as follows:

XOR(A, B) = A . B’ + A’ . B = (A+B) . (A’+B’) = XOR(B, A)

Eg:

A = 10101010

B = 11101101

C = 01000111 -> C = XOR(A,B)

XOR is denoted as ‘⊕’.

There are some tricky information about The XOR Operation:

- If you XOR something with same thing “again” it becomes itself.

Eg: You can check the following on Python3 interpreter:>>> hex(0x02 ^ 0x01) '0x3' >>> hex(0x03 ^ 0x01) '0x2' - There are many other rules of the XOR operation:

>>> 0x02 ^ 0x01 == 0x01 ^ 0x02 True >>> 0x02 ^ 0x02 0 >>> hex(0x02 ^ 0) '0x2' >>> (0x02 ^ 0x04) ^ 0x01 == (0x01 ^ 0x02) ^ 0x04 True

3. Padding Oracle Attack Under The Hood

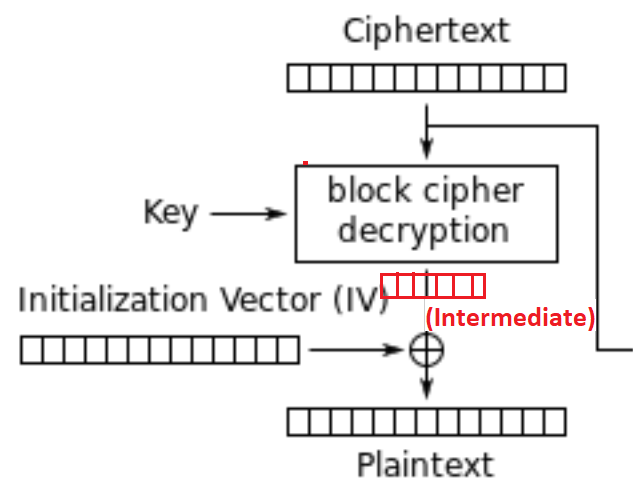

Let’s remember decryption of the AES-CBC:

3.1. The Trick: Finding The Intermediate and The Plaintext Blocks

Let’s zoom-in to an important place in the decryption scheme:

This part of Decryption Scheme is known as “Intermadiate State”. If we can find Intermediate Block then we can find Plaintext block by XORing with previous block (In this case with IV, because this block is the first one).

As seen on screenshot above we can create the following equation:

Intermediate_Block = Decryption(Current_Ciphertext_Block)

Current_Plaintext_Block = Intermediate_Block ⊕ (Previous_Ciphertext_Block)

If it is first block then:

Current_Plaintext_Block = Intermediate_Block ⊕ (IV)

So, equation for our first block which is on screenshot above can be like:

Current_Plaintext_Block = Decryption(Current_Ciphertext_Block) ⊕ (IV)

That means last byte of first block is:

Current_Plaintext_Block[-1] = Decryption(Current_Ciphertext_Block)[-1] ⊕ (IV)[-1]

We have the IV but we do not have “Decryption(Current_Ciphertext_Block)” output.

But server has the output of “Decryption(Current_Ciphertext_Block)”, like in boolean sql injections we use padding errors to find out output of Decryption(Current_Ciphertext_Block) then we use equation to find plaintext.

To do some math and playing with equations, let’s define some things:

- P: Plaintext => The secret message that we want to recover as an attacker.

In our demo application which is on github and explained on first part of this blog post; first block is used as IV, all rest is ciphertext

- C: Ciphertext => Something we have, the output of our cipher.

- IV => We have, first block of data we have.

- K: Key => It is necessary to decrypt ciphertext with IV by passing within cipher decryption function.

- C_P: Ciphertext_Prime => Modified ciphertext block.

- P_P: Plaintext_Prime => Decryption output of our custom input.

- N: Block_Size => Number of bytes.

- X[i]: ith byte of X (X is a block, ciphertext or plaintext…)

3.2. Algorithm of The Attack

Let’s say we only have 8 bytes (Steps would be same for 16 bytes as well, 8bytes is chosen to have less steps in this blog post) long of a ciphertext. The data we have would be in the following ‘merged’ format: 8_Byte_of_IV+8_Byte_of_First_Block

Step by step Cracking

-

Split the ciphertext into 2 equal 8-bytes of data. First would be the IV, second would be the first Ciphertextblock.

-

Create a blank IV (full of zero bytes).

-

Iterate each byte of IV from right to left.

-

Change that byte from 1 to 255 (from 00 to FF) then send the merged IV+block to the server (Oracle).

-

Until you do not get a padding error; continue (Stop when padding is valid).

-

When you get a valid padding you can guess intermediate byte by using the explanations on sections 3.2.1-3.2.4 of this blog post. When you find all of the bytes of the intermediate block then you can do XOR operation with ‘original IV’ in order to find the plaintext block.

-

If there are more blocks you can do same by looking ‘one previous block’ of ciphertext rather than the IV.

Let me cover once more what happens at the back-end:

- Oracle Server decrypts ciphertext with the key which is stored at back-end then this output is named as INTERMEDIATE BLOCK.

-

Oracle Server calculates following equation to get “Plaintext_Prime”= (INTERMEDIATE BLOCK) ⊕ (IV)

-

Oracle Server then checks if the Padding of Plaintext_Prime is correct or not by using the PKCS#7 or PKCS#5 that I explained on previous blog post.

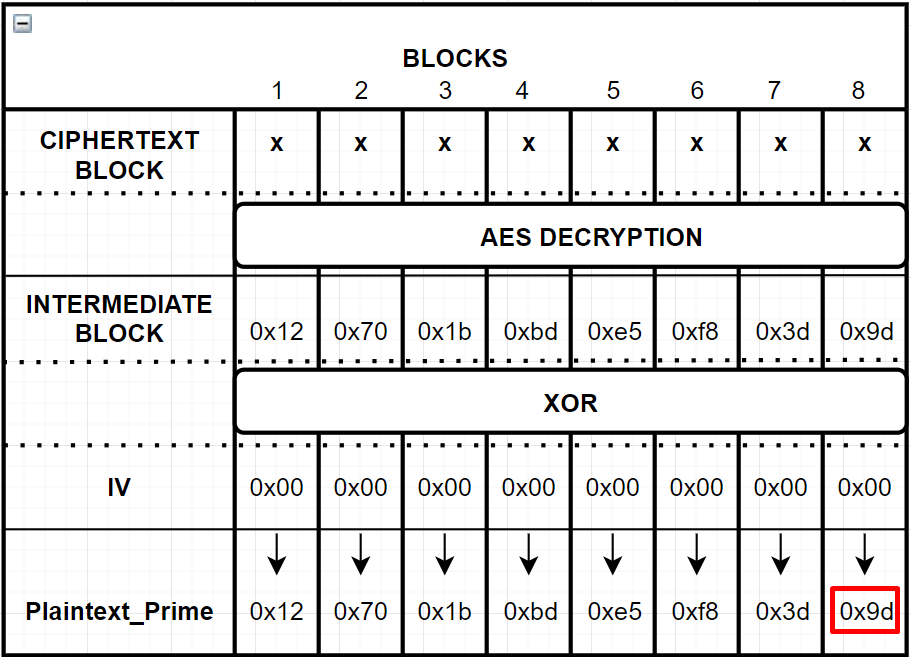

In the following sections I tried to visualize cracking step. We have the ciphertext block already but we do not use it except merging with the IV we manipulate then sending to Oracle Server. Hence I filled it with ‘X’ characters. So do not focus on Ciphertext on screenshots (XXXXXXXX).

Let’s define the variables:

Original IV: 0x79 0x15 0x68 0xd8 0x89 0x97 0x4e 0xf8

Decrypted value of Ciphertext block aka. Intermediate Value: 0x12 0x70 0x1b 0xbd 0xe5 0xf8 0x3d 0x9d

Oracle Server, stores that intermediate value but we are not able to know except sending crafted IV+ciphertext and receiving ‘padding errors’

I drew those screenshots on draw.io myself, you are free to use them in your presentations or anywhere.

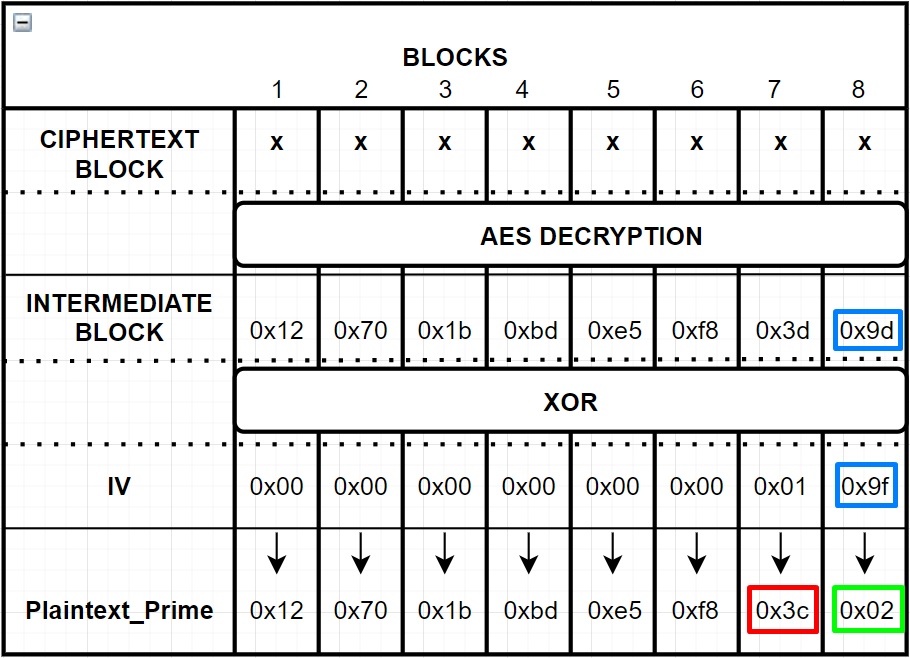

3.2.1. Cracking last byte of the intermediate block:

Let’s say we send following manipulated IV while iterating last byte of the IV from 1 to 255 (from 00 to FF):

We would get “Invalid Padding” result, because it does not follow PKCS#7 format since last byte of the Plaintext_Prime is 0x9d.

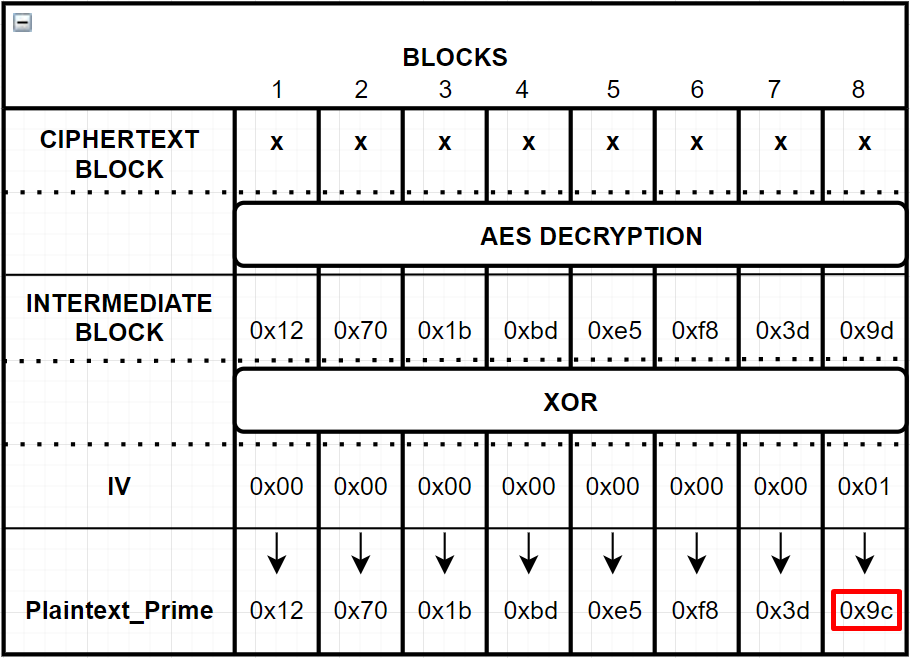

We would get “Invalid Padding” as a result again, because this one also does not follow PKCS#7 format since last byte of the Plaintext_Prime is 0x9c.

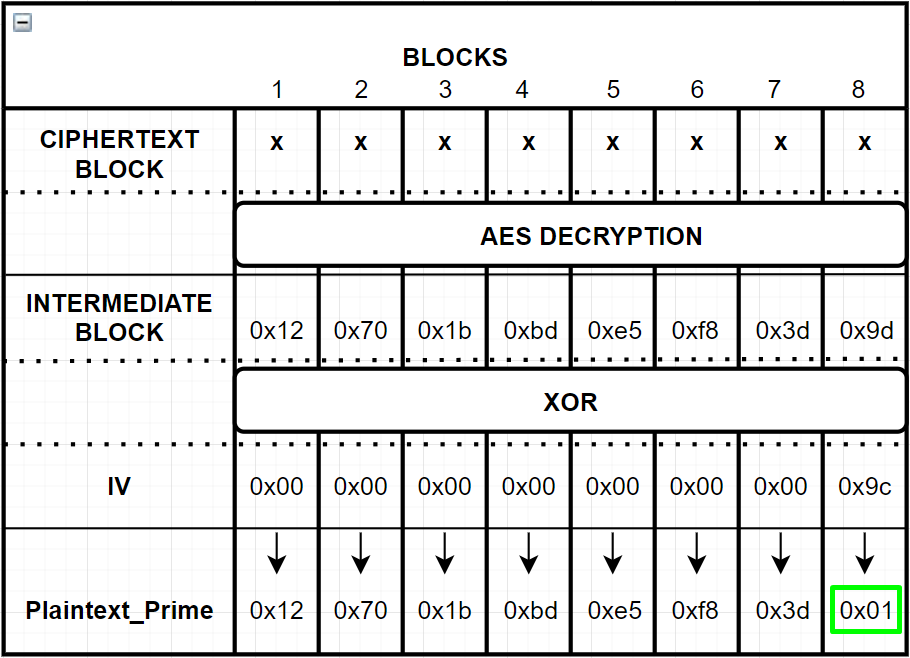

When we sent the manipulated IV above we get “Valid Padding” as a result! Because this one follows PKCS#7 format. I mean, the data has only 1 padding and it is 0x01.

Now let’s calculate the “last byte” of the Intermediate Block:

- We know last byte of the Plaintext_Prime should be 0x01:

Plaintext_Prime = [? ? ? ? ? ? ? 0x01]

- The IV we sent is 0x00 0x00 0x00 0x00 0x00 0x00 0x00 0x9c Then “last byte” of the Intermediate Block should be:

>>> hex(0x9c ^ 0x01)

'0x9d'

Then the IntermediateBlock is: [? ? ? ? ? ? ? 0x9d]

Now we know last byte of the intermediate block, so we can calculate last byte of the plaintext block by using following equation:

PlainText[-1] = IV[-1] ⊕ IntermediateBlock[-1]

Remember The Original IV:

0x79 0x15 0x68 0xd8 0x89 0x97 0x4e 0xf8

Then,

PlainText[-1] = 0xf8 ⊕ 0x9d

So;

>>> hex(0xf8 ^ 0x9d)

'0x65'

>>> chr(0x65)

'e'

So, we found that last character of the plaintext is ‘e’. Let’s continue…

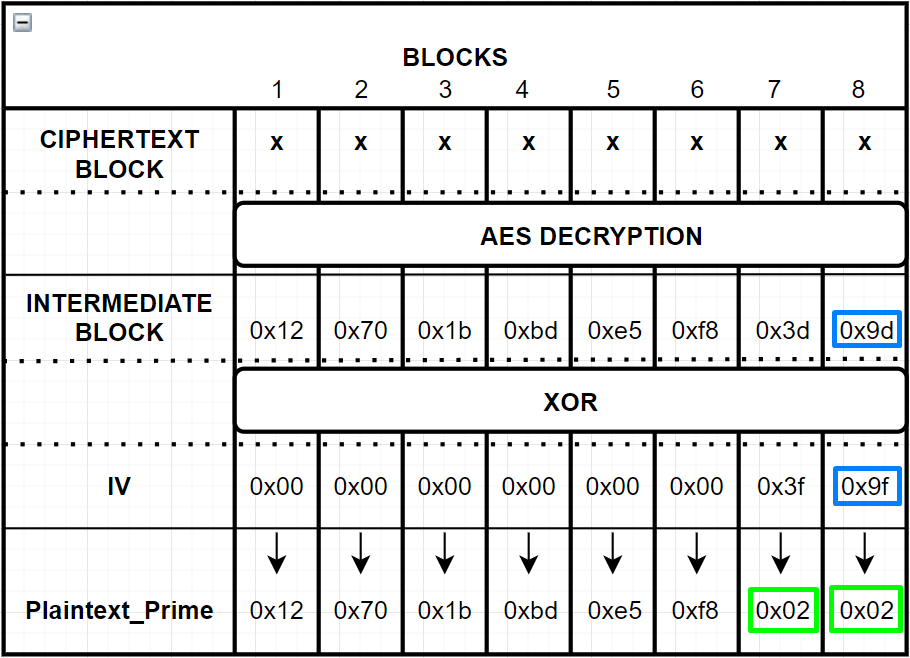

3.2.2. Cracking 2nd last byte of the intermediate block:

In order to find 2nd last byte of the intermediate block we need to get a “valid padding” as a response from Oracle Server.

To have that response the Plaintext_Prime needs to be in the following format:

Plaintext_Prime = [? ? ? ? ? ? 0x02 0x02]

We already know that last block of the Intermediate Block is 0x9d. In order to get a ‘0x02’ value, we need to set our manipulated last byte of the IV to the following value:

>>> hex(0x9d ^ 0x02)

'0x9f'

So the manipulated IV should be in the following format since ‘K’ needs to be iterated from ‘0x00’ to ‘0xFF’ to be sent to the Oracle Server.

Manipulated_IV = [0x00 0x00 0x00 0x00 0x00 0x00 ‘K’ 0x9f]

When we send the following we would get “Invalid Padding” as a result:

Until we get two ‘0x02’ values as last 2 values of Decrypted Value which is not shown to us, we would get “Valid Padding” as a result. Let’s say we sent ‘0x3f’ as the second byte and we got “Valid Padding”:

Then let’s calculate the 2nd last byte of the Intermediate Block.

- We know the last 2 bytes of the Plaintext_Prime should be 0x02:

Plaintext_Prime = [? ? ? ? ? ? 0x02 0x02]

- The IV we sent is 0x00 0x00 0x00 0x00 0x00 0x00 0x3f 0x9f Then “last byte” of the Intermediate Block should be:

>>> hex(0x3f ^ 0x02)

'0x3d'

IntermediateBlock = ? ? ? ? ? ? 0x3d 0x9d

Now we know last 2 bytes of the intermediate block, so we can calculate 2nd last byte of the plaintext block by using following equation:

PlainText[-2] = IV[-2] ⊕ IntermediateBlock[-2]

Remember The Original IV:

0x79 0x15 0x68 0xd8 0x89 0x97 0x4e 0xf8

Then,

PlainText[-2] = 0x4e ⊕ 0x3d

So;

>>> hex(0x4e ^ 0x3d)

'0x73'

>>> chr(0x73)

's'

So, we found that second last character of the plaintext is ’s’. Let’s jump to the cracking 8th byte, because all of intermediate steps would be in same process…

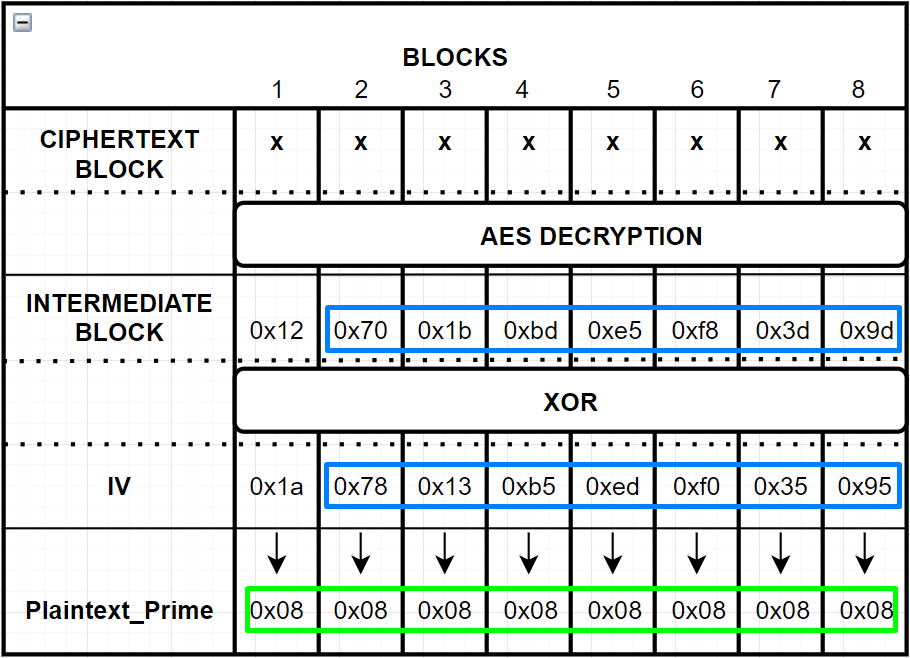

3.2.4. Cracking all bytes of the intermediate block (8-bytes length):

Then let’s calculate the first byte of the Intermediate Block.

- We know the 8 bytes of the Plaintext_Prime should be 0x08:

Plaintext_Prime = [0x08 0x08 0x08 0x08 0x08 0x08 0x08 0x08]

- The IV we sent is 0x1a 0x78 0x13 0xb5 0xed 0xf0 0x35 0x95. Then “first byte” of the Intermediate Block should be:

>>> hex(0x1a ^ 0x08)

'0x12'

Then;

IntermediateBlock = 0x12 0x70 0x1b 0xbd 0xe5 0xf8 0x3d 0x9d

Now we know every byte of the intermediate block, so we can calculate the plaintext block by using following equation:

PlainText[0] = IV[0] ⊕ IntermediateBlock[0]

Remember The Original IV:

0x79 0x15 0x68 0xd8 0x89 0x97 0x4e 0xf8

Then,

PlainText[0] = 0x79 ⊕ 0x12

So, we found that first character of the plaintext is ‘k’.

>>> hex(0x79 ^ 0x12)

'0x6b'

>>> chr(0x6b)

'k'

Let’s crack the whole plaintext;

>>> IV = [0x79 ,0x15 ,0x68 ,0xd8 ,0x89 ,0x97 ,0x4e, 0xf8]

>>> intermediate = [0x12, 0x70, 0x1b, 0xbd, 0xe5, 0xf8, 0x3d, 0x9d]

>>> plaintext = []

>>> ascii_plaintext = []

for i in range(len(IV)):

plaintext.append(hex(intermediate[i] ^ IV[i]))

ascii_plaintext.append(intermediate[i] ^ IV[i])

>>> plaintext

['0x6b', '0x65', '0x73', '0x65', '0x6c', '0x6f', '0x73', '0x65']

>>> ''.join([chr(byte) for byte in ascii_plaintext[::-1]])

'esolesek'

>>> # reversed(ascii_plaintext)

3.3. The Cracker Script

I wrote the cracker script as well as the vulnerable application for this blog post.

You can try this cracker script and vulnerable demo application by using the following commands:

git clone https://github.com/cemonatk/padding-oracle-demo

cd padding-oracle-demo/

python3 -m pip install -r requirements.txt

python3 vuln_server.py

On another terminal:

python3 cbc_cracker.py

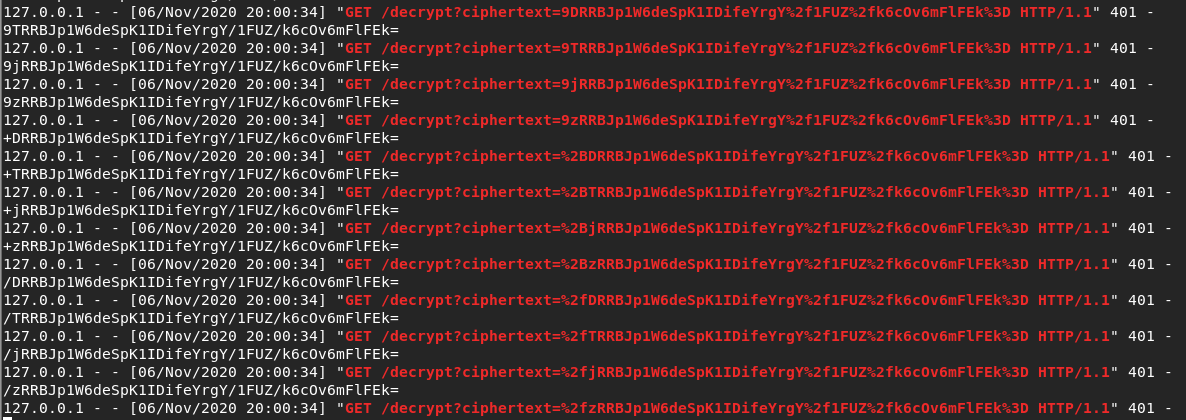

You can check the attack logs on the terminal of “vuln_server.py”:

The output is as the following GIF:

4. Penetration Testing aka. “Hunting The Padding Oracle Bugs”

4.1. White-Box aka. Spotting Bugs with Source Code Review

-

Check for “AES/CBC/PKCS5” or “AES/CBC/PKCS7” or “AES/CBC”

-

Checking if if application throws an invalid padding exception or message. Known ones like “BadPaddingException” or a custom one like “non-correct pad”… etc.

-

Dependency check: check if an old cryptography library is imported or not.

-

Check for decryption error handling places.

4.2 Black-Box

-

Check if there is something Base64 encoded that looks like a ciphertext. Check length of the decoded data if data%8==0 is True.

-

Check if there is hex encoded data, try same on option 1.

-

Replay data by manipulating last bytes of each block of data.

-

Observe the result if there is difference, blank page or a delay in response.

-

Check errors and exceptions:

.Net: Padding is invalid and cannot be removed

Java: BadPaddingException

4.3. Tools For Pentesters

- Padbuster

- Yapoet

- Padding Oracle Exploit Tool (POET)

- Padding Oracle Attacker

- Bletchley

- Poracle

- python-paddingoracle

5. Conclusion

- Dont rely on the solution steps mentioned here.

- Do not roll your own crypto never ever.

-

Do not use AES-CBC. Using CTR could be a better option, but it does not provide authentication hence it is vulnerable against Bit-Flipping Attacks. So, AES-GCM (Counter Mode of Encryption with Galois Mode of Authentication) could be a better option in this case.

-

Don’t give an error message like “Padding error”, “MAC error”, decryption failed” etc. Even you do not give errors/exceptions it could be possible guess padding errors by differentiating the response time. So it is better to look at 3rd option - Do not use CBC.

- You can check Authenticated Encryption for more.

6. Resources

Some additions to resources of the first part of this blog post.

- Practical Padding Oracle Attacks - BH Europe 2010 Presentation of Juliano Rizzo and Thai Duong

- http://netifera.com/research/

- https://blog.cloudflare.com/padding-oracles-and-the-decline-of-cbc-mode-ciphersuites/

- https://blog.cloudflare.com/yet-another-padding-oracle-in-openssl-cbc-ciphersuites/

- Padding Oracles Everywhere - ekoparty Security Conference 6th edition

- MS10 - 070 Post Mortem analysis of the patch

- Padding oracle in OpenSSL (CVE-2016-2107)

- Authenticated Encryption: Relations among notions and analysis of the generic composition paradigm